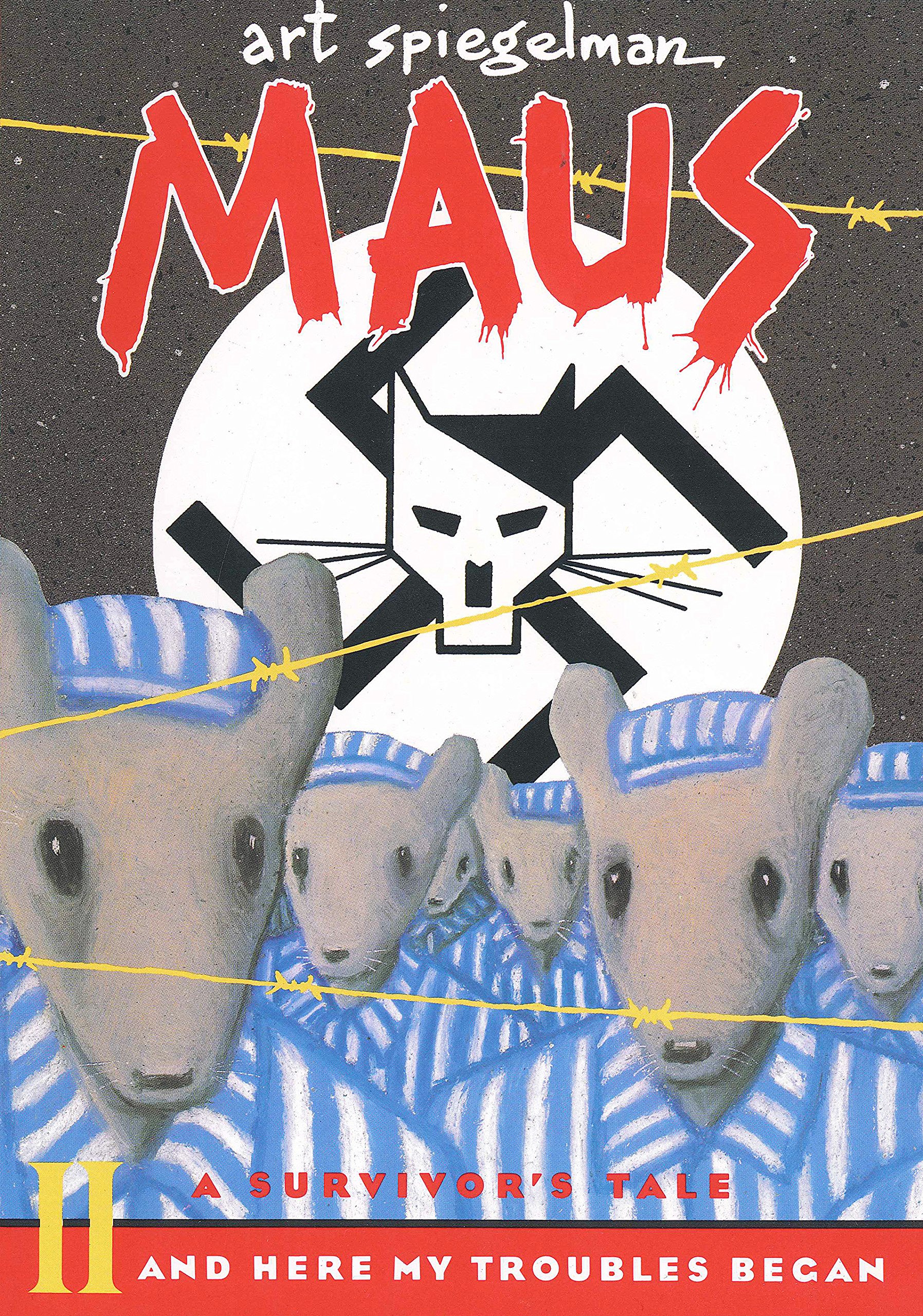

The Complete Maus

Book Description

In a world where cats hunt mice, one man's harrowing journey through the Holocaust unfolds, painted in haunting black and white. "The Complete Maus" captures the stark realities of survival, guilt, and the indelible scars of memory as characters wrestle with love, loss, and the specter of history. Art Spiegelman’s masterful storytelling transports you through the chaos of war and the intimate struggles of a father-son relationship, forcing you to confront the darkest parts of humanity. Can the bonds of family endure when haunted by such unimaginable trauma?

Quick Book Summary

The Complete Maus by Art Spiegelman is a groundbreaking graphic novel that intertwines the harrowing true story of the author’s father, Vladek Spiegelman, a Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust, with Art's own struggle to understand and portray that past. By depicting Jews as mice and Nazis as cats, Spiegelman creates a visual metaphor that underscores the predatory realities of Nazi Germany. The dual narrative oscillates between Vladek's memories of survival during World War II and the evolving, often tense relationship between father and son in the present. Through stark black-and-white art, the book unflinchingly depicts the horrors of war, the complexities of memory, and the lasting scars trauma imposes on survivors and their families. The Complete Maus is both a deeply personal memoir and a historical account, offering an unvarnished look at resilience, guilt, and the enduring impact of the Holocaust.

Summary of Key Ideas

Table of Contents

Survival and the Human Spirit

Maus opens with the strained relationship between Art Spiegelman and his father Vladek, whose stories from Holocaust-era Poland gradually emerge. Vladek’s account begins with pre-war life: his marriage to Anja, birth of their son Richieu, and burgeoning antisemitism. As conditions worsen, the family’s life unravels, leading them to face persecution, imprisonment, and the loss of many loved ones. Vladek’s ingenuity and determination help him and Anja endure internment and hideouts, surviving against incredible odds.

The Power and Problems of Memory

Art’s perspective frames Vladek’s recollections, bridging past and present. Their interactions reveal a complicated dynamic: Art struggles to connect with his father, whose trauma manifests as frugality, stubbornness, and emotional distance. The present-day narrative highlights generational differences and the challenge of legacy—particularly as Art tries to honor his father’s story while grappling with his own feelings of guilt, frustration, and inadequacy as a son and an artist.

The Intergenerational Impact of Trauma

The book explores the psychological cost of surviving inhuman conditions. Vladek is depicted as haunted by his experiences, suffering loss and survivor’s guilt, which deeply color his personality and relationships. The narrative does not shy away from presenting his flaws, emphasizing the enduring shadow cast by trauma—not only on survivors, but on those born after, such as Art. The suicide of Art’s mother, Anja, and the absence of his brother Richieu, who perished in the Holocaust, further illustrate generational pain.

Art and Representation of History

Maus emphasizes the difficulty of representing traumatic history, especially through the unique choice of the graphic novel format. Spiegelman’s use of animal allegories serves both as a distancing mechanism and a clarifying lens, allowing readers to confront the unimaginable horrors of the Holocaust. The stark black-and-white art style reinforces the bleakness of the events while providing a visual immediacy. The process of reconstructing memory is shown as incomplete and fraught, questioning the reliability and adequacy of historical storytelling.

Family, Guilt, and Forgiveness

Ultimately, The Complete Maus is not only a testament to survival and resilience but also an exploration of the power of storytelling itself. Through depicting his father’s survival, Spiegelman confronts the burdens and responsibilities of memory, forgiveness, and understanding within families marked by tragedy. The book asks what it means to bear witness—to maintain the memory of atrocities, to understand the enduring psychological wounds, and to pass these testimonies to future generations, ensuring that history is neither forgotten nor repeated.

Download This Summary

Get a free PDF of this summary instantly — no email required.