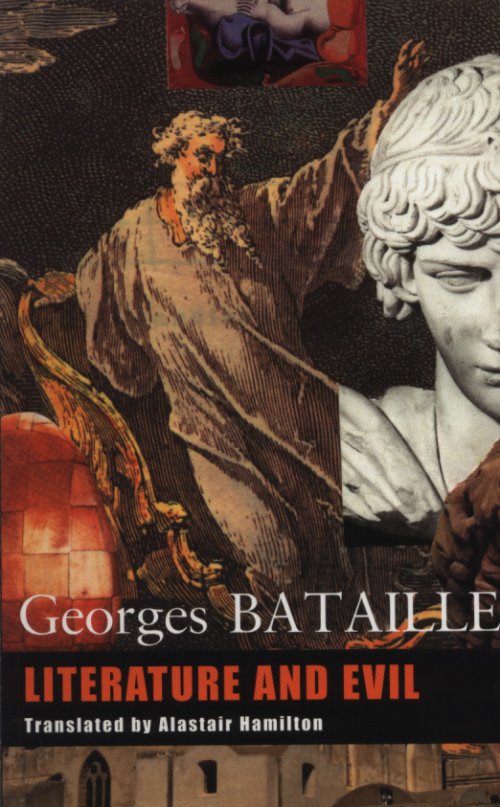

Literature and Evil

Book Description

What if the line between literature and the darkest corners of human experience isn’t just blurred but shattered? Georges Bataille’s 'Literature and Evil' plunges into this provocative abyss, exploring the intricate dance between creativity and moral transgression. Through a riveting analysis of literary giants, he reveals how the act of writing can serve as a gateway to forbidden pleasures and existential dread. With insights that challenge the very essence of art and morality, this book ignites a thrilling conversation on the nature of evil itself. Are we brave enough to confront the shadows that linger within our own stories?

Quick Book Summary

Georges Bataille’s "Literature and Evil" is a provocative philosophical inquiry into the relationship between literary art and moral transgression. Challenging the assumption that literature should uphold moral order, Bataille argues that genuine literature is inextricably linked to evil, not because it corrupts, but because it confronts taboo, ambiguity, and the limits of social norms. Through essays on writers such as Emily Brontë, Baudelaire, and Kafka, Bataille demonstrates how their work embodies the restless inquiry into human darkness. Rather than shunning evil, literature exposes and interrogates it, revealing a vital connection between creativity and forbidden desire. Bataille suggests that to fully understand literature—and ourselves—we must confront the unsettling presence of evil woven into both art and existence.

Summary of Key Ideas

Table of Contents

The Necessity of Evil in Literature

Bataille opens by challenging the conventional expectation that literature should reinforce moral values. Instead, he provocatively claims that literature is fundamentally bound to evil. Evil, for Bataille, is not simply wrongdoing, but the willingness to transgress boundaries, to question social taboos, and to resist the reduction of experience into tidy moral categories. This stance places literature at odds with institutions seeking order, establishing it as a realm of risk—a site where ideas both dangerous and liberating can flourish.

Transgression and Creativity

Focusing on the works of various literary figures, Bataille scrutinizes how writers such as Sade, Kafka, Baudelaire, and Emily Brontë grapple with evil. These authors’ creations are not straightforward affirmations of vice, but complex meditations on ambiguity, suffering, and the limits of human understanding. Their writings reflect the intrinsic unrest of the human spirit, often presenting evil not as a villain to be vanquished, but as an obsessive force that shapes identity, art, and society itself.

Ambiguity and Moral Complexity

Bataille develops the idea that true creativity requires a willingness to trespass into forbidden territory. He argues that by confronting the taboo and the abject, literature becomes a space where the reader and writer alike experience a kind of sacred violation. This transgression does not merely shock for its own sake; it questions the foundations of morality, authority, and civilization, inviting us to see evil as an essential aspect of creative illumination and existential inquiry.

The Role of Forbidden Desire

Desire is central to Bataille’s view of literature and evil. He sees forbidden desire—whether sexual, violent, or existential—as a force underlying both literary creation and human experience. Literature, he claims, allows us to explore these desires safely, or at least less dangerously, by transforming them into art. By engaging with texts that expose us to our own shadow, we increase our awareness of what it means to be human, embracing our complexity rather than denying it.

Literature as a Challenge to Morality

Ultimately, Bataille posits that literature’s engagement with evil is not simply nihilistic or destructive. Instead, it is an act of courage and honesty, necessary for any authentic confrontation with reality. Literature does not provide easy answers or reinforce conventional morality. Instead, it compels us to look unflinchingly at what society would rather repress, expanding our understanding of both art and the human condition. Bataille’s work remains a bracing call to confront the shadows without which neither literature nor life can be complete.

Download This Summary

Get a free PDF of this summary instantly — no email required.