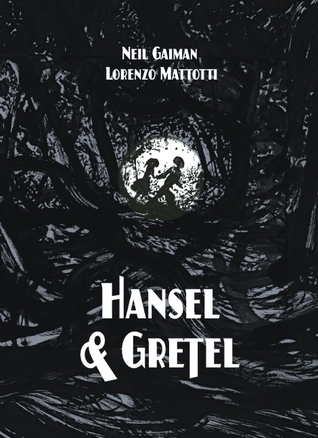

Hansel and Gretel

Book Description

Lost in the dark woods, a brother and sister must navigate a web of danger where innocence meets the sinister. With hunger gnawing at their bellies and the shadows whispering secrets, Hansel and Gretel discover a house of impossible sweetness—one that hides a terrible truth. As they face a witch with wicked intentions and the bonds of family are tested, survival becomes a desperate game of wits. Every step deeper into the forest risks not just their lives but their very souls. Will they escape the clutches of darkness, or will they become part of the tale's chilling legacy?

Quick Book Summary

Neil Gaiman’s retelling of "Hansel and Gretel" is a dark, atmospheric rendering of the classic fairy tale, enriched by evocative illustrations. The story follows siblings Hansel and Gretel as they are abandoned in a foreboding forest after their impoverished parents make a desperate decision in the face of famine. Driven by fear and hunger, the children stumble upon a seemingly magical house made of sweets, only to be ensnared by a cunning, child-eating witch. With wit and courage, Gretel outsmarts the witch, freeing herself and her brother. Gaiman’s version deepens the emotional resonance and psychological complexity, highlighting themes of resilience, trust, and the ambiguous line between safety and danger. Ultimately, the children must rely on each other and their resourcefulness to escape the darkness—both literal and metaphorical—that threatens to consume them.

Summary of Key Ideas

Table of Contents

The Loss of Innocence

Hansel and Gretel opens with a somber image of a family struggling against famine. Their parents, desperate and fearful, contemplate the unthinkable: abandoning their children in the woods to ensure their own survival. This decision fractures the bedrock of trust, sending Hansel and Gretel into a world where the familiar has turned unfriendly. Gaiman emphasizes not just the physical hunger that haunts the siblings, but also the emotional hunger for security, love, and hope—a subtle thread running through the narrative.

Survival Through Cunning and Courage

As Hansel and Gretel navigate the deep, shadow-laden forest, they face a series of trials meant to test their resolve. Starvation and fear become recurring adversaries, yet the siblings remain united, relying on wit and resourcefulness. Hansel’s strategy of leaving a trail and Gretel’s enduring courage establish the importance of ingenuity in the face of overwhelming odds. Gaiman’s storytelling paints the landscape itself as a living, menacing presence, further heightening the tale’s sense of foreboding and uncertainty.

The Peril of Temptation

The children’s discovery of the witch’s gingerbread house serves as a turning point. What appears as a sanctuary of abundance and sweetness quickly reveals itself as a sinister trap. The witch, embodying predatory evil beneath a veneer of hospitality, imprisons the children with intent to consume them. Temptation—represented by the edible home—serves as both salvation and danger: it offers momentary reprieve, but at a steep, hidden cost.

Family Bonds and Betrayal

The siblings’ struggle with the witch distills the story’s core conflict: the victory of courage and cleverness over raw power. Gretel’s quick thinking leads to the witch’s demise, reversing the dynamic of predator and prey. Gaiman explores the intricacies of fear and resourcefulness, framing Gretel’s heroism not as fearless but as forged in desperation. Their escape is less a triumphant return than a hard-won reclamation of agency, shadowed by the trauma of their ordeal.

The Ambiguity of Good and Evil

Upon their return home, Hansel and Gretel’s experience in the forest lingers, subtly altering their understanding of the world and of themselves. Family bonds, once broken by betrayal, are reforged out of necessity and forgiveness. The tale closes with the acknowledgment that innocence lost can give way to a different form of strength—one tempered by hardship but no less powerful. Gaiman’s version refuses to flatten good and evil, instead suggesting that survival often blurs the lines between them, leaving the siblings—and readers—aware of the complexities beneath every fairy tale ending.

Download This Summary

Get a free PDF of this summary instantly — no email required.